“Kaci Rodriguez knew her son was struggling mentally. His behavior was increasingly impulsive. He was becoming more easily distracted. And he was having more trouble with academic work and behavior issues at his elementary school. When she brought her concerns to his teachers, they often replied, “Oh, he’s just being a boy,” or, “Give him time.” But Rodriguez could tell something more profound was going on.

“I felt I had lost my child,” she said. “I had nowhere to turn.”

Her growing anxiety eventually prompted Rodriguez to seek help from mental health services. But getting her son evaluated took time. “The lack of access to mental health services is a huge problem where we live,” she said. Where she lives—Roswell, New Mexico—is a town of nearly 48,000people located in the high desert plains in the southeast corner of the state.

Eight months passed before Rodriguez could get her son an evaluation. He was diagnosed with ADHD and placed in the moderate to severe range of the condition. And it was recommended he be placed on medication.

Getting a prescription was also a challenge. Pediatricians are few and far between in Roswell, according to Rodriguez, and wait times to get an appointment are lengthy.

But once the meds kicked in, “the difference was like night and day,” Rodriguez said. “I felt like I had my boy back.”

The difference was also reflected in her son’s schoolwork, as his grades rose from failing to C’s and B’s.

The whole experience left Rodriguez with the lasting impression that finding mental health access for children shouldn’t be so difficult. “Parents in this situation don’t know what to do,” she said. “Teachers don’t know what to do either. They haven’t been trained for this.”

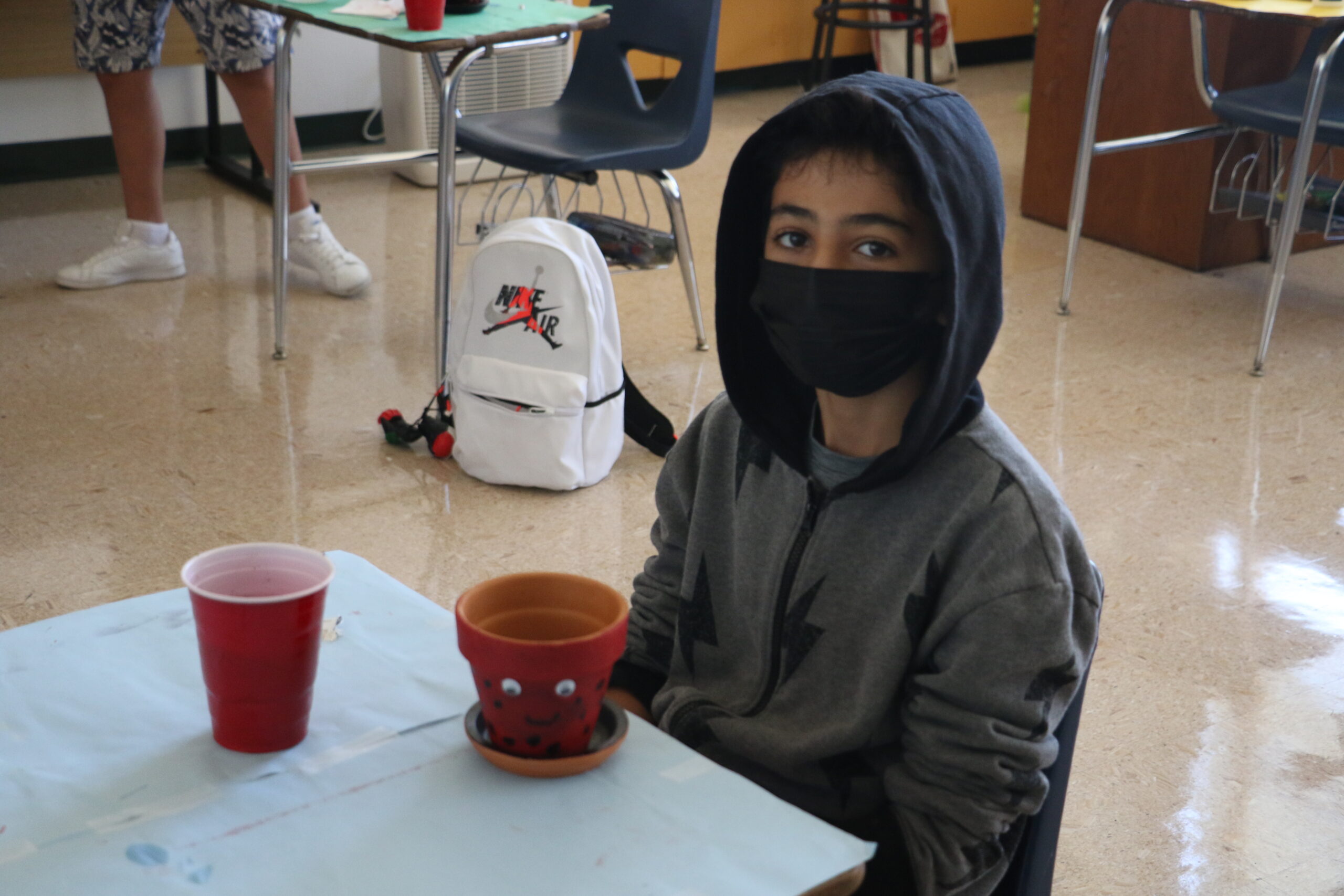

Her experience motivated her to go back to school to get certified as a special education teacher. She completed her certification and now serves as a resource teacher at Del Norte Elementary School in Roswell.

It also persuaded Rodriguez that when her son transitioned from elementary to middle school, they should find a school that offered an educational approach, commonly called community schools, where the school acts as a hub for accessing a wide range of student and family services, including mental health services.

“We specifically selected Sierra Middle School because of its community schools program,” she said.

Rodriguez is not alone in linking her child’s mental health struggles, and the lack of access to treatments, to the need for more schools to adopt the community schools approach.

In the aftermath of the tragic school shootings in Uvalde, Texas, in 2022, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona testified at a congressional hearing in May 2022 that his department’s 2023 budget would prioritize mental health supports for K-12 school children, and he linked that effort to expanding the number of community schools nationwide, according to K-12 Dive.”

Read the full story here.